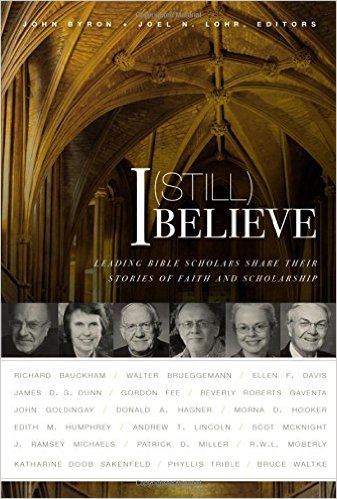

I (Still) Believe: Leading Bible Scholars Share Their Stories of Faith and Scholarship

A Denver Journal Book Review by Denver Seminary Professor Dr. M. Daniel Carroll R.

John Byron and Joel N Lohr, eds., I (Still) Believe: Leading Bible Scholars Share Their Stories of Faith and Scholarship. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2015. $24.99. Paperback. 249 pp. ISBN 978-0-310-51516-6.

This volume would be a helpful resource for anyone of Christian faith, who is employed in or aspires to a career in biblical scholarship. It is not uncommon to hear of those, of the past and in the present, who have forsaken their convictions because of academic work on the biblical text and research into its sociocultural and historical backgrounds. The purpose of the editors in organizing this volume is to provide counter portrayals of significant scholars in both the Old and New Testaments, who have wrestled in their work with their faith, but who have maintained—even deepened—it through their studies and teaching.

Toward this end, the editors—John Byron of Ashland Theological Seminary and Joel N. Loer of the University of the Pacific—enlisted eighteen senior scholars (some now retired) to share personal testimonies of their journeys. These are evenly divided between those in Old Testament (Walter Brueggemann, Ellen F. Davies, John Goldingay, Patrick D. Miller, R. W. L. [Walter] Moberly, Katherine Doob Sackenfield, Phyllis Trible, Bruce K. Waltke) and those in New Testament (Richard Bauckham, James D. G. Dunn, Gordon D. Fee, Beverly Roberts Gaventa, Donald A. Hagner, Morna D. Hooker, Edith M. Humphrey, Andrew T. Lincoln, Scot McKnight, J. Ramsey Michaels). Each one was asked to weave into their narrative the story of their call into academia, ways in which research may have threatened or enhanced their faith, the influence of their involvement in church life, and any closing words of advice for emerging scholars.

Each chapter is authored by a particular scholar, and these tend to be ten to a dozen pages long. These vignettes are a fascinating read. This reviewer personally knows several of these individuals, so some of the glimpses “behind the curtain” were especially interesting. In their introduction the editors mention two items most of these eighteen scholars share. The first is the impact of professors, who modeled a passion for the Bible and gave solid encouragement along the way. The second is that almost all grew up in an environment of faith and Bible study that laid the groundwork for their life work; most look back in appreciation of that heritage, even as they have left it behind or reframed matters.

Both aspects are important. For the established scholar who may read this volume, these memories of the positive effect of professors (whether in the classroom or study) are a good reminder of the need to guide and inspire those under our care. The task of mentoring should be part of our calling and can serve as the foundation for a fruitful legacy. It also is sobering to see how many were raised in conservative homes, where prayer, Scripture reading, and regular church attendance were part of the rhythms of family life. Today, in a Christian context of growing biblical illiteracy and decreasing congregational loyalties, could tales such as these be repeated? Without that underpinning of yesteryear, which set the course for careers in biblical scholarship, will we ever see again a generation like that on display in this collection?

All eighteen scholars believe the movement into scholarship shaped their Christian faith beneficially. In several cases the open environment of the institutions where they studied or taught and/or the hospitable spirit of mentors meant that critical thought was not perceived as something threatening to be avoided. Rather, those places and people fostered exploration of new approaches and difficult questions. There are a couple of instances, however, of those who found themselves in more traditional settings. Unfortunately, there they endured suspicion and attack during the era of the ‘battle for the Bible’ in the 1970s and 1980s and its aftermath. All feel that academic study has oriented them to read the text rightly—that is, according to appropriate literary genres and in a suitable relationship to historical intent. Inerrancy and overly literalistic interpretations as defined within very conservative circles are not considered viable.

At the same time, the contributors speak of the limitations of arid critical study and the importance of walking with God (whether on their own or within church contexts) in their scholarly endeavors. The spectrum of ecclesial involvement that is mentioned—not all the contributors do—is impressive. Church affiliations include the United Church of Christ, the Anglican and Episcopalian communions, the Orthodox tradition, and the Assemblies of God, Baptist and Presbyterian churches.

Two other issues deserve mention. The first is the trajectory of the female scholars in this volume. They have been pioneers for women in the fields of biblical studies and feminism. Theirs especially are testimonies of perseverance and grace. The second is the transparency of the contributors regarding the tragedies and joys of their personal and family lives, experiences that have affected who they are and what they do. These are testimonies shared in sincerity and humility. Scholars, too, are just ‘regular folk.’

My assumption is that each reader of I (Still) Believe will have favorites among the eighteen contributors, and I suspect that parts of these chapters surely will resonate with their own experiences in the guild. Because my work is in the Old Testament, I found myself particularly drawn to the autobiographical stories of the Old Testament contributors. Others will be drawn in other directions.

However one may evaluate some of the critical stances taken by these authors, no one can question the genuineness of their words. This kind of window into the thoughts and lives of believing critical scholars can serve as a constructive feature in contemporary discussions about the relationship between Christian belief and criticism, a topic that has generated much heat lately within evangelical scholarship because of the high profile of some who have embraced critical stances. These sorts of debates have been ongoing for over two centuries. What books such as I (Still) Believe do is to remind everyone that the coordination of academics and faith is complicated, and that these challenging tensions have a human face.

Daniel Carroll R., PhD

Distinguished Professor of Old Testament

Denver Seminary

January, 2016