Duchamp & Picasso: He Was Wrong

A Denver Journal Review by Denver Seminary Professor Douglas Groothuis

Ronald Jones (Author), Daniel Birnbaum (Editor), Annika Gunnarsson. Duchamp & Picasso: He Was Wrong. Paperback. Walther König, Köln; Bilingual edition, 2013. 140 pages.

This and another recent book have made much of the rivalry and antipathy between Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Marcel Duchamp, (1887-1968), two of the most influential, iconoclastic, and controversial artists of the twentieth century, although Picasso was immeasurably more popular and wealthy. (See also Larry Witham, Picasso and the Chess Player: Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and the Battle for the Soul of Modern Art [2013].) Picasso and Duchamp did not like each other; neither did they share a philosophy of art (if Picasso even had one). Hence, when Picasso heard that Duchamp had died, he promptly and laconically said, “He was wrong.” Had Duchamp outlived Picasso, the epithet (or something like it) probably would have been repeated. There was no meeting of minds (or paints or sculptures) to be found here between the Spaniard (who settled in France) and the Frenchman (who settled in America). This volume was published on the basis of an exhibit at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden (as are many art books).

This and another recent book have made much of the rivalry and antipathy between Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Marcel Duchamp, (1887-1968), two of the most influential, iconoclastic, and controversial artists of the twentieth century, although Picasso was immeasurably more popular and wealthy. (See also Larry Witham, Picasso and the Chess Player: Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and the Battle for the Soul of Modern Art [2013].) Picasso and Duchamp did not like each other; neither did they share a philosophy of art (if Picasso even had one). Hence, when Picasso heard that Duchamp had died, he promptly and laconically said, “He was wrong.” Had Duchamp outlived Picasso, the epithet (or something like it) probably would have been repeated. There was no meeting of minds (or paints or sculptures) to be found here between the Spaniard (who settled in France) and the Frenchman (who settled in America). This volume was published on the basis of an exhibit at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden (as are many art books).

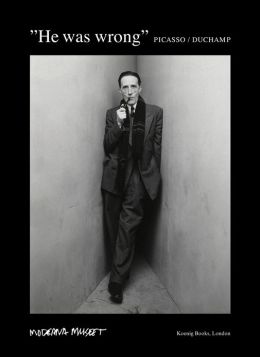

But before exploring the ideas and images of this book, I must explain its eccentric, if winning, format. It is structurally two books in one, with two black-and-white photographic front covers of equal prominence. There is no back cover and there are two spines, neither of which is labeled—making it difficult to find on a book shelf (and I write as someone always losing my books). One finds a cover with Picasso’s face, a close up, with hand on head—and those eyes. Within this part of the book is a short essay on Picasso (in both Swedish and English), a short essay on the works included, and a concluding set of images of his paintings. One can then turn the book over, find another front page with a photograph of Duchamp; this, too, features an essay (in Swedish and English), a short essay on the works included, and a concluding section of his paintings and other works (such as the famous “ready-mades”). Or as the book advertisement more concisely says, “The book is appropriately divided in two halves separated by a reverse binding.” The book does have a continuous pagination, starting with the Picasso side. The unique form of the book fits the content nicely, since Picasso and Duchamp opposed one another in many ways.

There is no real linear or thematic connection between their thoughts, lives, or art—apart from Duchamp’s early and short-lived association with cubist painting, a form that Picasso developed more fully. (Whatever it really meant is hard to ascertain). Hence, the book causes the antipodes to face each other only through opposition. But what was this classic conflict about? One may easily surmise that these denizens of modern art had affinities, given their general rejection of tradition and willingness to experiment with new forms of expression. But they did not.

The essence of the feud centered on the respective artists’ views of art itself. To use classical categories (made famous by Friedrich Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy), Picasso was Dionysian, celebrating the untutored eye beholding expression of his unfettered artistic self. He painted voluminously, likely painted more than any painter before or since. He bragged, “Give me a museum, and I will fill it.” He did not want people to think much about his paintings, but simply to experience them (and buy them for vast sums). Ironically, of course, as of 2003, there are about four hundred books on Picasso’s art, according to historian Paul Johnson. This is to be expected given his prodigious productivity, radical shifts in style (the blue period, the pink period, the different iterations of cubism, and much more), his relation to other artists, how his outrageous, perverse, misogynistic, and narcissistic life related to his art, and so on. Duchamp taunted Picasso as “retinal”—all image and no thought. He leveled the same judgment about Impressionism. His conception or art was more cerebral, however off-putting and bizarre it may have been. (Duchamp is famous for, among other things, his submitting a urinal for an art show—which was not juried—and calling it “fountain.” This was one of only twelve ready-mades he ever produced—if that is the right word.) His later passion for chess only embellished this ethos. Duchamp would not even acknowledge the greatness of Picasso, and, in fact, snubbed him in an interview, saying he was more interested in a lesser known painter.

Duchamp’s most well-known painting is “Nude Descending a Staircase,” which was recently represented on a US “forever” stamp. This was originally shown at the epical Armory Show in New York in 1913, where avant-garde works were prominently displayed to the delight, disgust, and bewilderment of the art world. Duchamp sought to disarm and deconstruct the very idea of art as a special realm for the master who produces privileged art works. In that, he rejected the concept of “fine art,” which Paul Johnson understands as the felicitous paring of skill and innovation, worked out by a craftsmen over a lifetime (Art: A New History of Art [2003]). He, like Picasso was an amoral nihilist, an atheist who thought that man-made objects had no fixed or determinative meaning. He was deeply ironic and opaque in expression, thus finally thwarting any intellectual approach to art. This is distressingly obvious in the recently released book of interviews with Calvin Tompkins called Marcel Duchamp: The Afternoon Interviews (Badlands Unlimited, 2013).

Duchamp was hopeless opacity. This is simply because the intellect requires concepts and propositions to assess, if knowledge is to be won. It also demands intellectual virtues, the chief of which is the search for truth. Duchamp’s endless turgidity without lucidity makes for insanity at worst and inanity (however gnomic) at best. One can find a certain brilliance in “Nude Descending a Staircase,” given its originality and skill in execution. Yet it was intended to destabilize meaning and subvert traditions without offering anything solid in their absence. Duchamp also violated sexual norms with abandon in many of his works; in paintings, photographs, and installations. He hinted at his own bisexuality as well. For him, the past was only prologue for perversity, in life and in art.

Picasso was known as a painter, although he also made sculptures and engaged in just about every other form of visual art-making. He produced paintings from a very early age and continued to paint at a rapid rate (about one per day) the rest of his life, painting up till his death at age ninety-two. Picasso wanted his viewer to see his work as visual, graphic, sensorial. He despised theorizing, since he believed that it undermined the painting as a painting.

This disagreement between two mavens of modern art has profound consequences for the pursuit of truth and beauty. Neither held a coherent, rationally defensible worldview. Picasso openly turned on God after the death of his young sister and never looked back. Art historian and critic, Hans Rookmaaker, in Modern Art and the Death of a Culture [InterVarsity, 1970], calls him a nihilist, and with good reason. Duchamp was elusive to the point of obscurantism, but we can know that he, too, rejected any God-given meaning in life or art. While Picasso rejected analysis in the quest for meaning, Duchamp championed the mind, but at the expense of knowledge. Both, thus, end up in the same philosophical ditch; neither can, on the basis of their worldviews, give art or the human condition any meaning or direction. Nevertheless, as humans, they seek some manner of meaning in their thoughts and lives. This, in God’s world, is inescapable, since all humans are made in the image and likeness of their Creator. But, as Francis Schaeffer said, “Man is a rebel” against God, and, therefore, is a rebel against both the external and internal world (see Proverbs 8:36). Yet these rebels, in art or elsewhere, continue to be meaning-seeking beings. One hopes that more of these rebels (however celebrated in their rebellion and nihilism) end up submitting to reality and respond accordingly, in art and in all other areas of culture.

Douglas Groothuis, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy

Denver Seminary

June 2013