Lies My Preacher Told Me: An Honest Look at the Old Testament

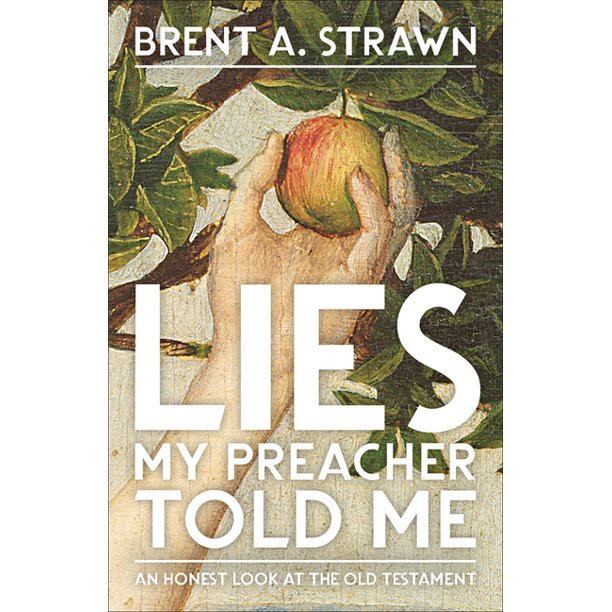

Strawn, Brent A. Lies My Preacher Told Me: An Honest Look at the Old Testament. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2021. xi + 116 pp. Paperback, $16.00. ISBN 9780664265717.

Old and New Testamentlers alike should be encouraged by the recent spate of books upholding the riches and ongoing relevance of Israel’s scriptures today. Such books include John Goldingay’s Do We Need the New Testament? (IVP Academic, 2015); Matthew Richard Schlimm’s This Strange and Sacred Scripture (Baker Academic, 2015); and Brent A. Strawn’s The Old Testament Is Dying (Baker Academic, 2017). As of 2021, they also include a sequel of sorts from Strawn: Lies My Preacher Told Me: An Honest Look at the Old Testament.

Inspired by James Loewen’s Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong (2nd ed.; The New Press, 2018), Lies My Preacher Told Me seeks to set the record straight concerning ten of the most pervasive mistruths about the Old Testament among Christians today (Lies in the title is somewhat tongue in cheek). They include the following, side by side with Strawn’s responses (which he calls “clarifications”):

Mistruth 1: The Old Testament is “someone else’s mail.” (3)

Clarification 1: The Old Testament, no less than the New, is Christian Scripture. (9)

Mistruth 2: The Old Testament is a boring history book. (11)

Clarification 2: The Old Testament is about far more (and far less) than history, and it can be endlessly fascinating to those with eyes to see, ears to hear, and patience to read. (17)

Mistruth 3: The Old Testament has been rendered permanently obsolete. (19)

Clarification 3: The Old Testament is and remains a lively and useful part of Scripture and a crucial resource for Christian reflection. (29)

Mistruth 4: The Old Testament God is mean . . . really mean. (31)

Clarification 4: God in Scripture (not just the Old Testament) is deeply upset about injustice and sin; God’s judgment of those things is in service to setting the world aright. (39)

Mistruth 5: The Old Testament is hyper-violent. (41)

Clarification 5: Both Testaments—Old and New—contain violent passages; violence is not, however, part of God’s initial purposes in creation, nor is it the end goal of the divine plan. Instead, the Bible manifests attempt to limit and constrain violence, encouraging us to contain our own proclivities to hyper-violence. (52)

Mistruth 6: David wrote the Psalms [and other simplistic historical assertions such as “Moses penned the Pentateuch” or “Solomon wrote Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs”]. (55, 61)

Clarification 6: Historical background information is often important, but is often not nearly as important as people think. Who, exactly, wrote what and when and where is far less important than what, exactly, is written. (63)

Mistruth 7: The Old Testament isn’t spiritually enriching. (65)

Clarification 7: The Old Testament is spiritually enriching in countless profound ways. (71; cf. esp. 2 Tim. 3:16–17, which originally referred to the Hebrew scriptures)

Mistruth 8: The Old Testament isn’t practically relevant. (73)

Clarification 8: The Old Testament is useful for Christian practice in a whole host of ways, on a whole host of topics, and from a whole host of sources. (82)

Mistruth 9: The Old Testament Law is nothing but a burden, impossible to keep. (83)

Clarification 9: The Old Testament Law is not impossible to keep [cf., e.g., Exod. 35–40; Deut. 30:11–14; Job 1:1, 8; 2:3; Matt. 5:20; Phil. 3:4–6]; the Law is crucial because it is a primary means by which a right relationship with God, fellow humans, the earth, and its creatures is maintained. (90)

Mistruth 10: What really matters is that “everything is about Jesus.” (93)

Clarification 10: The Old Testament is not “all about” Jesus Christ; even so, the Old Testament is and remains a primary witness to the God that Christians know as Triune: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. (103)

This brief review, of course, can’t engage each of Strawn’s arguments in detail, but perhaps it suffices (and whets the reader’s appetite) to suggest that the book’s value far exceeds its size. In fact, chapters 4 and 5 are well worth the purchase of the book alone. There, Strawn not only insists that we should better appreciate the realities of divine anger and judgment in the Bible (not least because they demonstrate God’s deep concern for justice!), but he also avows that our discomfort with these “benevolent, even therapeutic” notions says a good deal about us. “To put a fine point on it,” he writes, “perhaps we don’t like divine judgment and wrath, wherever we find it in Scripture, because we are perfectly comfortable with injustice and sin, because we—unlike God—are indifferent to evil” (35). Or, as Strawn even more provocatively puts it later on,

If we are offended by the Bible’s violence, it is possible that the Bible (personified for a moment) might look back at us and say: “Who are you calling violent?” Our own brands of violence are far more graphic, more brutal, and more effective than anything the biblical authors could ever have imagined. Death by sword is one thing, but the biblical authors had no extended magazines, armor-piercing bullets, carpet bombs, biological and chemical weapons, or nuclear warheads to cause maximum damage, killing the most amount of people with minimal physical effort. Neither did the biblical authors spend their hard-earned money and leisure time on entertaining themselves with violence. (49)

Of course, Strawn’s work is not without its weaknesses, even if they are isolated and hardly detract from its value. One such weakness is Strawn’s slightly confusing discussion of modern-day Christians as addressees of the Bible: “So, no, the letters to the Corinthians were not addressed to [us]. They, too, are ‘someone else’s mail.’ But, yes, on the other hand, these letters are addressed to [us] because they are now part of Christian Scripture” (5). A more helpful way of putting this, I think, following John Walton and others, is that the biblical documents were not written to us but were certainly written for us (cf. Rom. 15:4; 1 Cor. 10:11; 2 Tim. 3:16–17). A second such weakness is Strawn’s incomplete treatment of Hebrews 8:13 on pages 20–21—a text that seems to suggest, at least at first, a complete discontinuity between old and new covenants (and, therefore, Old and New Testaments). And a third weakness is Strawn’s unexplained assertion that “there is no ‘works righteousness’ in the Old Testament or Judaism” (86). Finally, I did notice a glaring typo in Marcion’s life span on page 25 (i.e., “85–160 BCE”), as well as a surprising number of editorial inconsistencies with commas, m-dashes, and semicolons in parenthetical citations.

Still, this is a delightful and enlightening little book that rectifies not only the most popular misunderstandings of the Old Testament today, but also a few of the New. It does so in a highly creative, colloquial, and sometimes even comical way as well. For example, Strawn states on page 70 that “biblical faith is fundamentally and at root a communal matter. It concerns the polis as much as it does the pious.” The author also dubs the golden calf debacle in Exodus 32 as “Calfgate,” describing it as “the religious equivalent of committing adultery on one’s wedding night” (87). And while discussing what it would be like if the prophecy of Isaiah 7:14 were fulfilled only by Jesus, he imagines the following conversation between Isaiah and King Ahaz:

“Don’t worry about a thing, Ahaz: seven hundred years from now everything will be a-okay!”

“Gee, Isaiah, thanks . . . I guess. So what do I do about the armies at the gate?” (101)

Such humor is easily on par with that of Jim Gaffigan or Brian Regan—two of today’s funniest comedians.

On a much more serious note, the ecclesial focus of the book, together with its short chapters and questions for discussion, make it an ideal resource for any small group wanting to explore the Old Testament and its role in the Christian life today. While not explicitly designed for use in academic contexts, it nevertheless could be used as a primer or as supplemental reading in Old Testament survey courses as well, whether at Bible colleges, Christian universities, or seminaries and divinity schools. That is especially true since many students, even at the graduate level, import much of what they have learned in church (including various “lies their preachers told them”) into their academic studies.

Brandon C. Benziger, MDiv, ThM

Associated Faculty

Denver Seminary

February 2022