Live Not By Lies

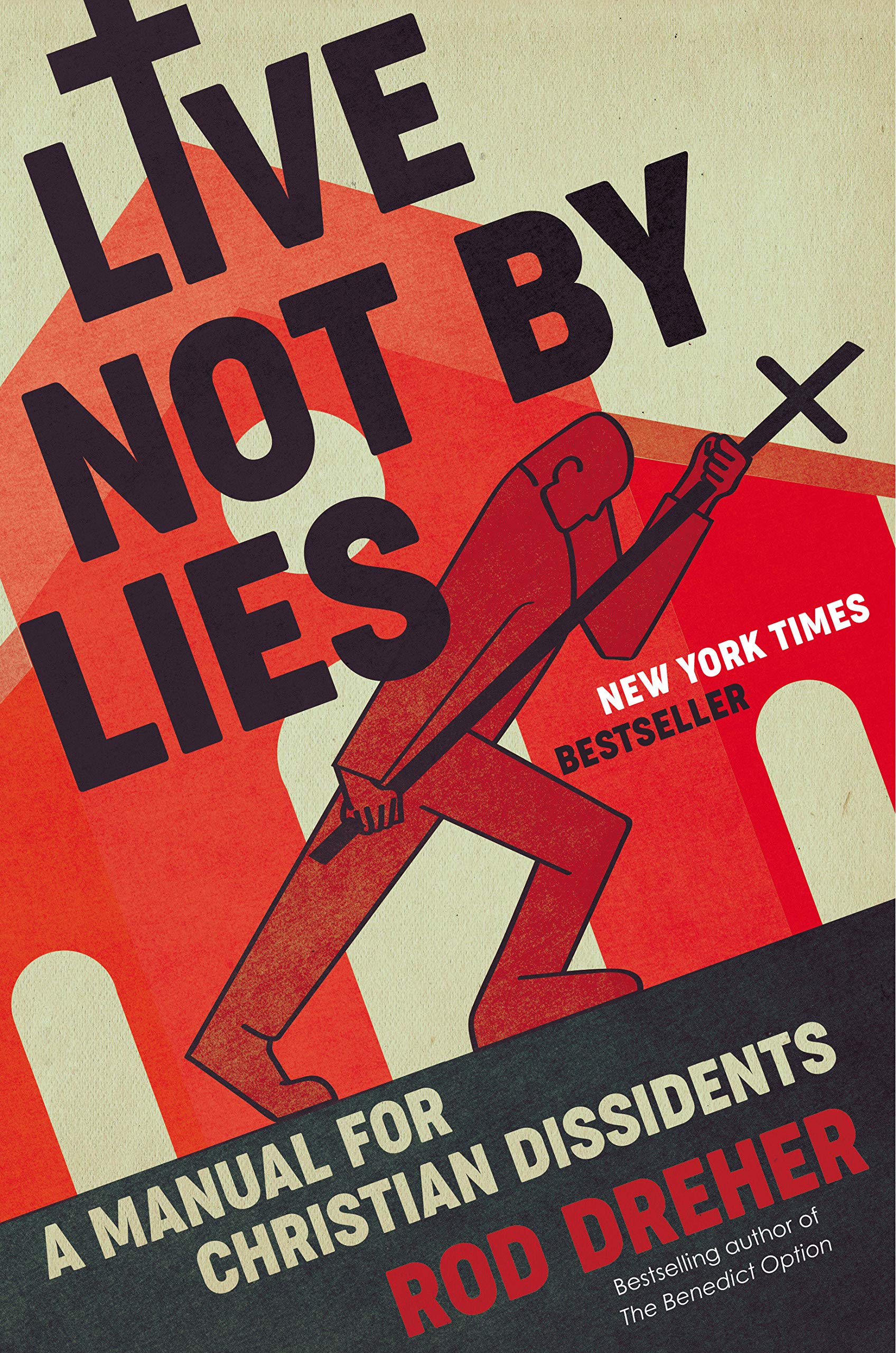

Rod Dreher, Live Not By Lies, New York: Sentinel, 2020. 240 pages. $27.00. ISBN: 978-0593087398.

Rod Dreher’s book Live Not By Lies is a brief but challenging examination of the parallels between totalitarianism in Soviet bloc countries and the rise of what Dreher calls a soft totalitarianism in the United States. His thesis is predicated on the belief that a steady shift from a Judeo-Christian worldview to a postmodern, secular one has begun. Though the higher echelons of society have the biggest influence on the country, Dreher notes that Americans – typically the younger generations – are also primed for a soft takeover. The most alarming thing about the new worldview is that, like the Marxist worldview that undergirds it, it comes with brown-shirted brow-beating. Dreher’s book examines the worldviews that are opposing Christian and classical liberal belief. The book also offers practical ways to resist the onslaught of progressive ideology.

The book is split into two parts. The first part is called “Understanding Soft Totalitarianism.” This section explores what soft totalitarianism means, why it’s here, how it acts as a religion, and how Big Tech plays a major role. Dreher draws heavily on Russian, Czech, and Slovak sources. The book title comes from a phrase used in an essay written by the Russian dissident and author of Gulag Archipelago Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Through interviews with ex-Soviet bloc dissidents – whether in interviews or from writings or other documentation – Dreher builds a case for parallels between the rise of soft totalitarianism in America and the rise of totalitarianism in Eastern Europe.

One of the strongest chapters in this section is entitled “Our Pre-Totalitarian Culture”. This chapter highlights the cultural similarities between our times and the pre-October Revolution times. For a portion of the chapter, Dreher relies heavily on Hannah Arendt’s book The Origins of Totalitarianism. The observations that Arendt makes – writing in the 1950’s – should be rather alarming to most Americans. Dreher notes the key aspects of Arendt’s arguments. First, loneliness and social atomization will precede a dictatorship. The more the individual feels isolated, the more likely they are to accept something that will give them a sense of belonging. Second, many Americans – the younger generations in particular – do not trust their institutions. This was clearly seen on both sides in the previous two elections. Where Democrats spared no expense in overturning Trump’s election in 2016 (with pushes to get rid of the electoral college), Republicans marched on Washington in 2021 with the assumption that the election had been stolen. Third, people, as they become more isolated, are more willing to toe a party line, even if it means believing a lie. A good example of this is the 1619 Project. Though the project is full of outright lies and shoddy historiography, it has already been taught in forty-five hundred classrooms (Dreher, 37).

The second part of the book is called “How to Live in Truth” and gives practical ways that Christians can not only prepare to resist in the future but to resist in the now. Dreher offers some very helpful, practical ideas in this section. In an age where many believe that truth is relative, Christians need to affirm and speak out the truth. This isn’t merely our truth, but objective truth that is reflected by reality around us. Dreher’s insight on maintaining a cultural memory is keen. The true history of Western civilization, of the United States, can be carried on through those who not only know its history but who have actively participated in preserving it. Dreher suggests that the American church will steadily have to move underground. By preserving a cultural memory, Christians can not only pass this history and culture on to their kids, but to those who feel ostracized by progressivism. The State may be able to take Bibles, guns, and other things, but it can’t take memory. Dreher also notes that in several ex-Soviet bloc nations, the cultural memory that was preserved through the travail of totalitarianism has been lost by people who simply don’t care and who take their liberties and freedom for granted.

Dreher also stresses the importance of the family unit. One of the major reasons for the decline of Western civilization has been the destruction of the family unit. Dreher believes that learning and catechesis happens at the dinner table and in the living room. Families should not let education happen at school only. Dreher tells of several Czech and Slovak families that resisted tyranny by fighting as a family. Vaclav and Kamila Benda, Czech dissidents, helped their family through the totalitarian reign over their country by exposing them to culture, having conversations about movies they watched, reading Scripture together, and being honest with each other. One thing that the Benda children remember fondly about their parents is that they didn’t succumb to pressure or give up.

This book is very well written and researched. Not only are there extensive footnotes, but much of the information that Dreher uses is from interviews. While many other reviews have noted that the book is biased or ‘too conservative,’ Dreher’s approach leaves one feeling that he is not fighting for a partisan line but for an entire civilization. There’s no question Dreher is conservative – he’s a senior editor at The American Conservative – but that shouldn’t stop anyone from reading the book. Dreher draws on so much historical content and cultural observation that the last thing the reader should feel is voting for Trump Dreher has several things to say about modern conservatism, as well. He believes that they can no longer rely on the labels ‘woke’ or ‘politically correct’ as a way of summarizing their political opponents. More than that, he suggests that Trump, though on the other side of the political spectrum, is still a personality that wants completely loyal followers. With this in mind, Dreher may have gone into more depth on how progressive ideology actually hampers sexual and racial progress.

Dreher states his case firmly without overstating it. The reader will find it very compelling and alarming, but not panicky. Dreher writes as though the culture is already a foregone conclusion and that Christians should prepare for a mostly underground existence. And while some may find this point to be hyperbolic, the historical parallels are too unsettling to ignore. Whether conservative or liberal, the reader must realize that modern progressive movements are not in the best interest of liberties and equality; bi-partisan resistance in Christian circles is needed now more than ever. May all Christians of all political sensibilities find this book enlightening.

Steven Wierenga

MA Apologetics and Ethics

Denver Seminary

January 2022