New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology and Exegesis

A Denver Journal Book Review by Denver Seminary Distinguished Professor of New Testament, Craig L. Blomberg

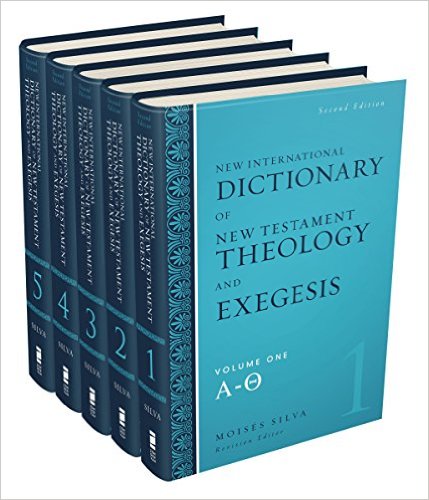

Moisés Silva, ed. New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology and Exegesis. 2nd ed. 5 vols. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2014. $249.99. 3635 pp. ISBN 978-0-310-27616-6

In 1978, the four-volume New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, edited by Colin Brown, was completed and released to well-deserved acclaim. It was both a translation and a substantial revision and expansion of the Theologisches Begriffslexicon zum Neuen Testament of 1967. Not only was it particularly well done, it was heralded as a welcome alternative to the massive and costly ten-volume Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, edited by Gerhard Kittel, with particularly streamlined sections on classical Greek and Septuagintal backgrounds of NT Greek words.

Thirty-six years later, Moisés Silva, formerly a NT professor at Westmont College, Westminster Seminary and Gordon-Conwell Seminary, has completed an extraordinary labor of love in thoroughly revising and updating Colin Brown’s work. Internet and computer-based searches are now so powerful that lexicography continues to advance in discoveries and understanding enough to necessitate this kind of second edition. Like Zondervan’s counterpart for Old Testament Theology and Exegesis, this volume not only adds the two extra words to its title, but plenty of extended focus on key texts with the words being studied, thereby justifying the additional words.

Entries are now in alphabetical order according to the Greek word families, but indexes keyed to Strong’s and Goodrick-Kohlenberger’s concordances make the work accessible for those who can’t find the words otherwise. The new structure avoids the problem of Brown, where largely unrelated Greek words were sometimes grouped together simply because they at times translated the same English word. But a sixty-page segment, repeated at the beginning of each volume, arranges a list of English concepts alphabetically, complete with their semantic domains in Greek, for those interested in the information that Brown’s structure provided. An entire final volume of indexes allows one to look up all references to Scripture and other ancient literature and all Greek and Hebrew words discussed.

Where Brown had short sections under each word group for classical Greek and Septuagintal uses, Silva simply has Greek literature and Jewish literature, allowing him to range even more widely and often expand each of those sections a little, though still nowhere to the length one found in Kittel. The NT sections are usually the longest, however, as in Brown, with distinctive foci of particular NT authors or books noted, along with a brief exegesis of the most important texts featuring the word group at hand. Prepositions are no longer treated in a separate appendix, as in Brown, but are incorporated into the alphabetical entries at the appropriate places. Many new words have been included, swelling the entries to about 800 in number with over 3000 Greek words treated. Comparisons with English translations usually reference the 2011 NIV, but sometimes they are contrasted also with the 1984 NIV, the NRSV, and one or two other versions, whereas the NETS is the standard point of comparison for the Septuagint.

Listing sample strengths of specific articles seems almost random, given the amount of rich, helpful material throughout these volumes. Silva rightly notes that no strong difference should be postulated between agapaÅ and phileÅ unless context dictates it (and probably John 21:15-17 does not). AiÅnios does usually mean “everlasting” in the NT, especially with heaven and hell, rather than “to the end of the age” as sometimes in the Old. Hamartia is the word for sin with the greatest semantic range, while parabasis without exception refers to a conscious transgression or trespass. EgeirÅ more consistently refers to resurrection than anistÄ“mi, even though both mean to raise up. The major distinctive of Jesus’ teaching of the basileia was not in the character of this kingdom, nor even in its eschatological timing but in its inseparability from his person. Boulomai and boulÄ“, when referring to God’s will or counsel, always denote “irrefragable determination” (1:528). GinÅskÅ and oida, the two main words for “know,” may refer to experiential vs. cognitive knowledge, respectively, but a large percentage of the time this is clear due to other contextual and syntactical features that demonstrate it, not any meaning inherent in the words themselves.

What makes something a true example of the gift of speaking in a tongue (glÅssa) is not some linguistic structure but an unintelligible utterance not attributable to the “excitability of human piety” (1:590) but to the work of the Spirit for God’s glory and worship. With Schreiner, the egÅ of Romans 7 may refer to every person, Christian and non-Christian alike. The image (eikÅn) of God “in” humanity may be a misnomer, since we reflect his unique mold throughout every part of our beings. Language about election (eklektos, eklegomai) refers to the after-the-fact realization that the people of God can take absolutely no credit for their existence as a new creation.

Genuine elpis (hope) “involves the abandonment of all calculations of the future” and “the submission of our wishes to the demands of the battle for life to which we have been appointed” (2:188). Where Paul and James at first seem to contradict each other on works (erga), Paul is fighting against the notion that they can lead to righteousness, while James combats a dead, fruitless orthodoxy. HÄ“suchios often does not mean absolute silence but a gentle, teachable demeanor; so probably in 1 Tim. 2:11-12, especially given its use that way in 2:2.

Key texts apply theos (God) to Jesus, showing the NT’s clear belief in his deity. All thlipsis (tribulation, distress) which the world thrusts on believers can be made meaningful only by understanding it in solidarity with Christ’s sufferings. “The decisively new and constitutive factor for any Christian conception of time is the conviction that, with the coming of Jesus, a unique kairos has dawned, one by which all other time is qualified” (2:590). KaleÅ (to call) should not be interpreted uniformly from one writer or speaker to the next. For Paul it may often be effectual; for Jesus, in the parables, it means to invite, and it can be refused. The apantÄ“sis (meeting) of 1 Thess. 4:17 is probably that of a welcoming party that will usher Christ back to earth in triumph.

The article on logos (word) is 43 pages, by far the longest in the set. What is unprecedented about this word’s use in the NT is that it refers to a human being who became fully incarnate. A mesitÄ“s (mediator) was normally “a neutral third party seeking to negotiate an agreement” (3:288) between two other conflicting parties. Jesus’ lack of neutrality may explain why this term is comparatively rarely used of him in Scripture. Jesus does not act against God’s revealed will in the nomos (Law) but does sharply challenge many common interpretations of it, and he inaugurates an era in which many of its injunctions, being fulfilled, are no longer applied identically. Jesus came in the likeness (homoiÅma) of sinful flesh not because he was less than fully human but because he was not sinful nor did he ever sin.

Greek church fathers uniformly understood the pistis tou Christou as containing an objective genitive (faith in Christ) rather than a subjective one (the faithfulness of Christ) despite the latter’s trendiness in many circles today. We, too, should probably follow the ancient wisdom here. Miracles can be signs (sÄ“meia) or pointers to faith but they will never compel it. “However, what finally and radically distinguishes Jesus’ miracles. . .is their eschatological reference” (4:288). Stoicheia (elemental spirits) for Paul probably partake both of the constituent elements of the universe in the context of worship, which for him would have meant demonic influence.

SÅma (body), pneuma (spirit), and psychÄ“ (soul) do not denote three separate parts of the human person, but there is a partial dualism of the material and immaterial that must be acknowledged. The pneumatikos (spiritual person) in 1 Cor. 2 is any true Christian; only in ch. 3 does Paul introduce a distinction among believers (with the sarkin/kos or fleshly person). Physis (nature) usually refers to God’s created order and cannot be used to relativize Paul’s teaching on homosexuality. Psuchos (cold) in Rev. 3:18 is positive just as warm is, given the two forms of water supply at Laodicea; only lukewarm is negative. “We should finally stress that ‘Son of Man’ and ‘Son of God’ do not form a pair of contrasting titles, denoting Jesus’ humanity and deity respectively” (4:546, under huios, “son”).

In works of such magnitude, there will inevitably be glitches. It does not appear there is old enough evidence to continue to assert that Gehenna was the perpetually burning garbage dump in Jesus’ day. Nor does it seem likely that men and women were segregated in the synagogues already during Second Temple Judaism. It seems hardly generalizable any more to say that almost all Jewish women were veiled in all public settings in the first century. The distinction between Peter and his confession as the rock (petra) on which Christ would build his church seems no longer necessary and is seldom elsewhere adopted.

Every once in a while post-NT developments in an area that drew its name from the Greek word under consideration are discussed at the end of an entry. The modern discipline of hermeneutics, for example, is touched on at the end of the article on hermeneuÅ—to translate or interpret. A final paragraph under deka (ten), describes the transition from voluntary giving to legislated tithing under Charlemagne in the eighth century. But there are no comparable reflections, for example, on the development of the Eucharist under eucharisteÅ (to give thanks) or liturgy under leitourgia (worship, cult ritual).

Not surprisingly, given the publication dates of the German and English predecessors to Silva, the works cited in his articles and listed in the bibliographies come disproportionately from the 1950s-70s. But he consistently adds well-chosen items from more recent years to the bibliographies and, though less consistently, interacts with some of them in the articles themselves. The number of typos, given the complexity of the material, is astonishingly small.

Few scholars who retire from an illustrious teaching and writing career would ever devote years on end to updating others’ works, as Silva has. We are massively in his debt for this extraordinary project and for a job very well done.

Craig Blomberg, Ph.D.

Distinguished Professor of New Testament

Denver Seminary

August 2015